[This post by Martin Smith]

A few years ago we deconstructed (in ten episodes) the remarkable chess painting created by Anton Rosenbaum in the years 1874 to 1880.

|

| © National Portrait Gallery |

There was much to talk about: the supposed chess event depicted; the initial disposal of the painting in a souped-up raffle; its 130 year journey from Mayfair to an outpost in North Wales (where it is currently on display); the artist himself (the rather dubious Mr Rosenbaum, of whom there was indeed a lot to be said); and of course the real characters portrayed playing or watching (even from up high on the back wall) the three games in progress. Art-geeks might also wonder just how Rosenbaum did it.

The dramatis personae runs from top-flight players of whom we have all heard, and perhaps have seen elsewhere (for example: Bird, Steinitz, Zukertort), through to lesser lights who names are now forgotten, and whose likeness might have been lost altogether but for Rosenbaum's magnum opus (it measured 6 feet by 4). Somewhere on this spectrum from perennial fame to peremptory oblivion sits the exotic Wordsworth Donisthorpe, installed - as his brand of libertarian politics would dictate - over in the right corner. He was a prolific pamphleteer, and the inventor of a primitive movie camera, and clearly has other things on his mind today. He was not in the chess-class of Bird et al, though he had a more than minor role in the chess politics of the time. We told his story before, so The Adonis (as he was wont to be called) will not detain us further.

As for others in Rosenbaum's mass-portrait...

...it would take a life-time of devoted labour to excavate the stories of them all, so it might seem rather perverse to add another who, though connected to the picture, is not actually represented in it. This, however, is what we are going to do in this extended sequence following-on from Mr Rosenbaum's Chess Picture. What gives this additional person an especially strong claim on our attention is that unlike all of the 47 chaps in Rosenbaum's tableau, she is a woman.

If it's not too much of a dance around our subject we will get to her with a side-step to the gent sitting it out bottom-left exuding rather more gravitas than his pictorial mirror-image in the corner opposite.

This is William Roberts Ballard (b. 1821- d.1904). He was American by birth and European by domicile, eventually settling in London (he appears in the 1861 census) via a stint in Italy - then a nation not yet unified as we more or less know it today. The Risorgimento concerned him so much that he wrote a little book (published in London in 1862) proposing a location for the emerging nation's capital - based he said on 10 years-worth of living there "including the eventful epoch of 1847 to 1849", and "frequent communication with Italians from all parts...for the past nineteen years". He opined that Rome would not be satisfactory as the seat of Government due to the "intrigues of the Catholic powers" via the Vatican, and its "unhealthiness". It should be instead "near the the borders of Tuscany...the land once governed by the illustrious Countess [n.b. - MS] Matilda...". For better or for worse his advice went unheeded.

Italy, or more precisely Naples, is important in our story, and will re-appear in the narrative; but for the moment its relevance is that it provided William Ballard with his wife: a local lady, Angelina née De Deo (1828-1895). There appears to have been three children, all born in Naples: the first was another William Roberts Ballard, born 29 March 1847.

William Roberts Ballard Junior (he died in London in 1933) may be seen in the back row of the Rosenbaum tableau, next but one along from Rosenbaum himself (the artist's self-portrait in profile).

That's a Mr Mackern between them, someone in the sunk-without-trace camp (sadly - though I'd be delighted to be shown to be wrong). Incidentally, there was another image of Ballard Jnr earlier in the Rosenbaum series, though we didn't know it at the time. It appeared when we mused (here) about the identity of the suave young buck standing over on the right in the snap below.

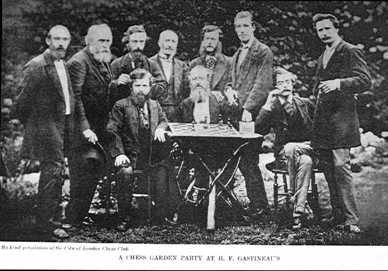

|

| From Sergeant's A Century of British Chess (1934) |

This captures a convivial moment from 1873 at one of Mr Gastineau's fabled garden parties, on this occasion in Peckham (Mr G. is in the centre of the photo, and third from the left in the back row of the Rosenbaum painting - again with the stand-out beard). But that is not The Adonis on the right (as was our tentative speculation in episode 8 of Rosenbaum), nor is it Mr Carslake Winter-Wood as suggested elsewhere. It is - as Tim Harding points out, in his indispensible Blackburne biography of 2015 - the 25 year-old W.R. Ballard Junior. The positive ID comes from a roughly contemporary source (details in the Notes below).

That evening several of Mr Gastineau's guests locked horns in a consultation game starting at 6.15 - played in the conservatory. Thus Potter, Coburn and Bussy took on Blackburne, De Vere, and Ballard (all but Bussy and De Vere appear in Rosenbaum). It was a dour struggle (the score is in Blackburne) with Black resigning after White's 59th, their 2Bs+R finally prevailing over Black's 2Rs after 30 moves of protracted end-game manoeuvre. At a rate of play regulated to 10, or perhaps 12 moves, per hour measured by sand glass (see note) no surprise that they saw the sunrise at 3.15am before the game was concluded - after nine hours of play (according to the report in The Field extracted by Tim); but no doubt there were agreeable refreshments along the way.

Chess-wise, then, Ballard Junior was a decent player - indeed, according to his obit in the BCM of October 1933, he was "looked on as one of the rising young players of England" - and in the thick of London chess society in the 1870s as we saw above, and then into the 1880s and beyond. He was with the venerable City of London Chess Club, and by the 80s he was also appearing on top board for St. George's C.C. Here is an example of his youthful resourcefulness - applied to no avail - in a fabulous game by Blackburne playing 10 opponents from the CoLCC simultaneously blindfold in 1872 (it is included in Tim Harding's comprehensive volume - on page 93). It was described as Blackburne's best blindfold game ever - note that it was adjourned after White's 21st.

Ballard Jnr was to follow his father's footsteps into the mouths of others and ply his Victorian-cum-Edwardian trade as, horror of horrors, a dentist - they were both listed as such in the 1881 census.

From 1909 - this lady is not for gurning.

|

What of the other Ballard children? There is a reference to another son in the Italian records: Harry, born on 30 August 1848, also in Naples. But he appears (as far as I can see) nowhere else in the historical documentation, so perhaps he was another marginal victim in the appalling toll of child mortality in the period - something else that will feature again in this account.

So we get to the last child of William Roberts Ballard Senior and Angelina, who was perhaps, after two sons, a case of third time lucky: it was a girl. She was born on the 9 January 1850, and christened Louisa Matilda. She became - as was said by the BCM in 1906 (p196) - "probably the strongest lady player in the United Kingdom".

|

| Mrs Fagan in 1898 |

Notes:

Details of the personnel in the 1873 Garden Party photo, from Hoffer in The Field of 31 December 1910, and referenced by Harding (2015): l to r., standing: J.Lovelock, Bernhard Horwitz*, William Potter*, J.J.Löwenthal*, Henry Down, Joseph Blackburne*, William Ballard jnr*. Seated: Wilhelm Steinitz*, Henry Gastineau*, Cecil De Vere.

The suggested rate of play for the consultation game comes from that given in Steinitz's notes to consultation games Blackburne* & Zukertort* v Potter* & Steinitz* at Mr. Eccles* chess party in Kensington on 17 June 1875, and B & P v S & Z at Mr Kunwald's* in New Burlington Street on 24 July 1875. See Adams (2014).

(*indicates shown in Rosenbaum's tableau of 1874-1880).

The Capital of Italy, and how to get it by William Roberts Ballard (1862)

Joseph Henry Blackburne - A Chess Biography by Tim Harding (McFarland, 2015)

Johannes Zukertort - Artist of the Chessboard by Jimmy Adams (New in Chess 2014)

Subsequent Episodes: Part 2: Mrs Fagan's Game; Part 3: Mrs Fagan's Game Resumed; Part 4: Mrs Fagan's Family Part 5: Mrs Fagan's Politics; Part 6: Another Mrs Fagan...and Her Politics. Part 7...And the Final "Mrs Fagan"

Johannes Zukertort - Artist of the Chessboard by Jimmy Adams (New in Chess 2014)

Subsequent Episodes: Part 2: Mrs Fagan's Game; Part 3: Mrs Fagan's Game Resumed; Part 4: Mrs Fagan's Family Part 5: Mrs Fagan's Politics; Part 6: Another Mrs Fagan...and Her Politics. Part 7...And the Final "Mrs Fagan"

For all chess history posts (including all the Rosenbaum episodes) in a previous incarnation go to the Streatham and Brixton Chess Blog History Index.

No comments:

Post a Comment